Trauma Treatment is the Goal.

Sexuality change is often the byproduct.

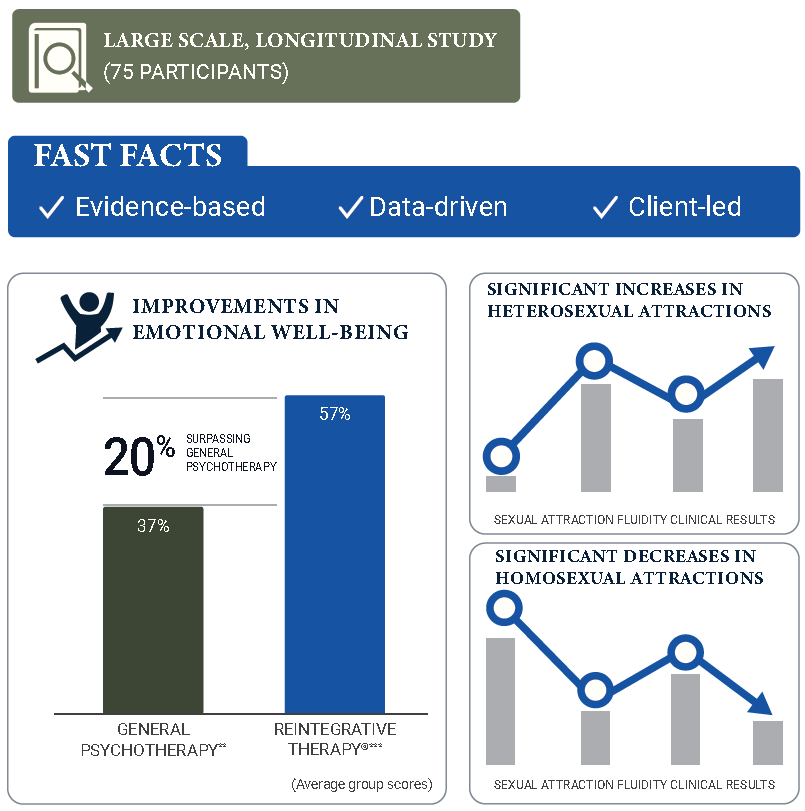

We know from large-scale, longitudinal evidence (Pela & Sutton, 2021) that Reintegrative Therapy® is associated with statistically significant decreases in same-sex attractions, increases in heterosexual attractions, changes in sexual identity toward a heterosexual identity, and increases in psychological well-being (e.g., decreases in anxiety, depression, and suicidality).

But why is sexuality change a spontaneous byproduct of trauma treatment? This may result from multiple factors.

Decades of research have shown that sexuality is fluid and can change for some people. The brain has the capacity to wire and rewire itself based on life experiences. According to the American Psychological Association (Storms, 1980), as well as other published scientific sources (Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012), a significant number of men who identify as homosexual sometimes report romantic and sexual attraction toward women.

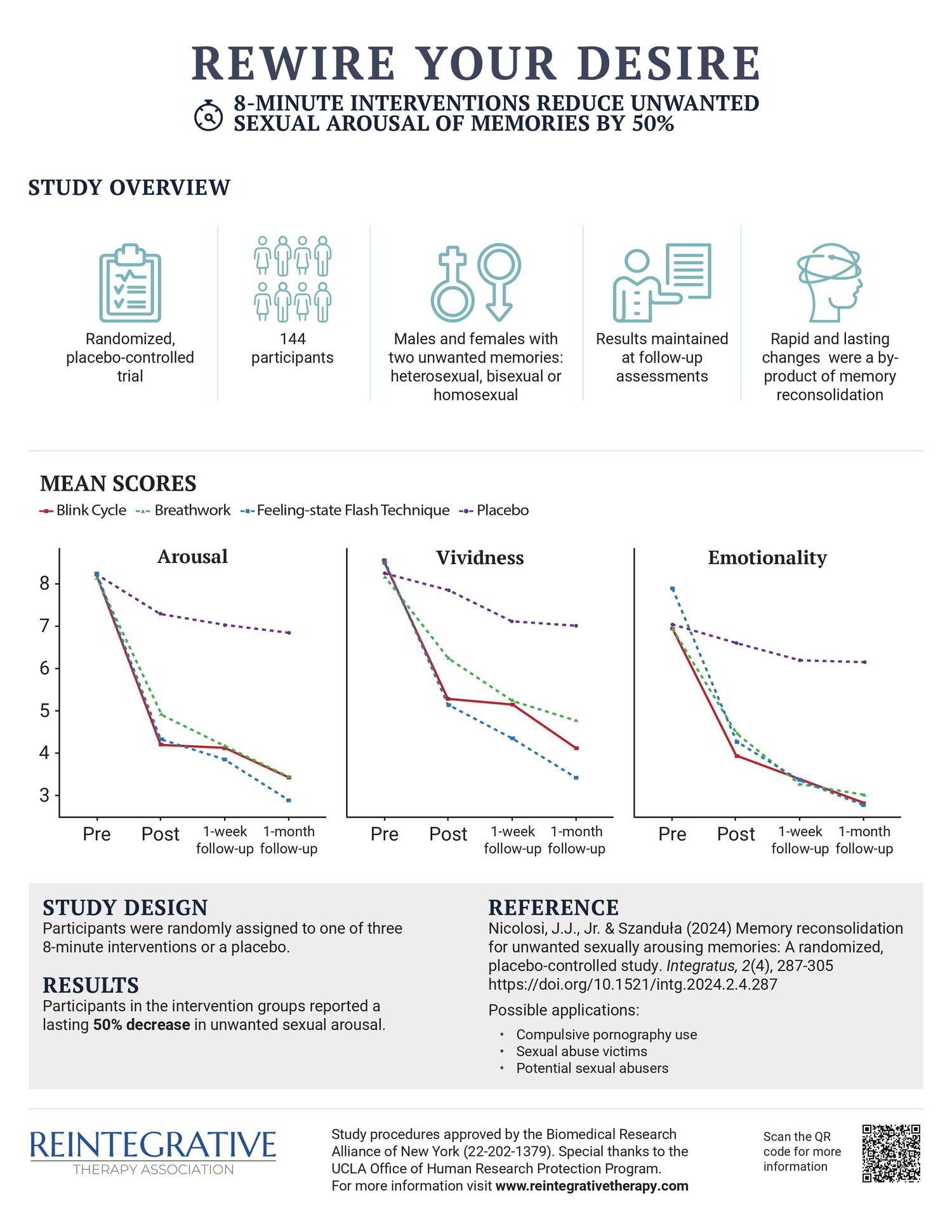

Results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (Nicolosi & Szanduła, 2024) indicate that brief interventions can decrease arousal in unwanted sexually arousing memories within minutes—and these changes appear to be enduring.

The APA has concluded that for some individuals, childhood sexual abuse has “associative and potentially causal links” to having same-sex partners in certain instances, based on research that included a 30-year longitudinal study of documented cases of childhood sexual abuse (Mustanski, Kuper, & Greene, 2014). Traumatic experiences can, for some individuals, subsequently affect sexuality (De Silva, 2001; Parent & Ferriter, 2018), and treatment of childhood traumatic memories has been shown to trigger significant, spontaneous changes in sexual attractions (Cornine, 2013).

Childhood relational experiences can influence individuals’ templates for attraction—one study found that adoptive daughters often chose husbands who resembled their adoptive fathers, if they had a positive father-daughter relationship (Bereczkei et al., 2004). This suggests that early emotional experiences help form unconscious “ideal partner” templates that can later influence who people find attractive.

Bilateral eye movements, sometimes incorporated by Reintegrative Therapists in treating trauma, have been shown to trigger spontaneous changes in clients’ sexual feelings, regardless of the client’s gender or sexual orientation (Bartels et al., 2018; Jebelli et al., 2018). Reintegrative Therapists sometimes incorporate a practice called “mindfulness,” which has also been demonstrated to trigger spontaneous changes in sexual feelings as a byproduct (Dickenson et al., 2020). In none of these approaches is a client encouraged to try to change their sexual feelings; in fact, attempts to change one’s sexual feelings could interfere with the process. These documented sexuality change mechanisms are completely non-volitional.

It should be noted that APA’s Ethical Principle E protects clients’ rights to self-determination (Behnke, 2004) and aims to enhance client autonomy. Limiting or interfering with client autonomy violates this basic principle. Reintegrative Therapists respect clients’ rights to set their therapy goals and access evidence-based trauma resolution methods that have been shown to trigger spontaneous sexuality changes as a byproduct. This distinction, among others, is why Reintegrative Therapy cannot be categorized as so-called “conversion therapy.”

For those interested in a review of more than 100 years of experiential evidence, clinical studies, and research demonstrating that it is possible for some men and women to shift along the sexual-fluidity spectrum, and that efforts to change do not typically result in harm, click below for an in-depth summary.

Click here for complete scientific references

Bartels, R. M., Harkins, L., Harrison, S. C., Beard, N., & Beech, A. R. (2018). The effect of bilateral eye-movements versus no eye-movements on sexual fantasies. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 59, 107-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.01.001

Behnke, S. (2004). Informed consent and APA’s new ethics code: Enhancing client autonomy, improving client care. Monitor on Psychology, 35(6), 80.

Bereczkei, T., Gyuris, P., & Weisfeld, G. E. (2004). Sexual imprinting in human mate choice. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 271(1544), 1129–1134. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.

Cornine, C. K. (2013). EMDR, sexual confusion, and God-image: A case study. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 32(1), 83-89

De Silva, P. (2001). Impact of trauma on sexual functioning and sexual relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 16(3), 269-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990123900

Dickenson, J., Diamond, L., King, J., Jenson, K., & Anderson, J. (2020). Understanding heterosexual women’s erotic flexibility: The role of attention in sexual evaluations and neural responses to sexual stimuli. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(10), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa058

Jebelli, F., Maaroufi, M., Maracy, M. F., & Molaeinezhad, M. (2018). Effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) on the sexual function of Iranian women with lifelong vaginismus. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 33(3), 325-338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2017.1323075

Mustanski, B., Kuper, L., & Greene, G. (2014). Development of sexual orientation and identity. In D. Tolman & L. Diamond (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 609-610). American Psychological Association.

Nicolosi, J.J., Jr. & Szanduła, J. (2024) Memory reconsolidation for unwanted sexually arousing memories: A randomized, placebo-controlled study

. Integratus, 2(4), 287-305 https://doi.org/10.

Parent, M. C., & Ferriter, K. P. (2018). The co-occurrence of asexuality and self-reported post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis and sexual trauma within the past 12 months among U.S. college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1277-1282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1197-7

Pela, C., & Sutton, P. M. (2021). Sexual attraction fluidity and well-being in men: A therapeutic outcome study. Journal of Human Sexuality, 12, 61-86.

Storms, M. D. (1980). Theories of sexual orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(5), 783-792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.5.783

Vrangalova, Z., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2012). Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 85-101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y

Reintegrative Therapy®

can trigger shifts in sexual feelings

Memory Reconsolidation for Unwanted Sexually Arousing Memories

A randomized placebo-controlled trial

Three experimental interventions appear to be effective in decreasing arousability, vividness, and emotionality of two unwanted sexually arousing memories simultaneously. These interventions may benefit therapeutic contexts involving sexual abuse, paraphilic disorders, or other sexually compulsive behaviors.